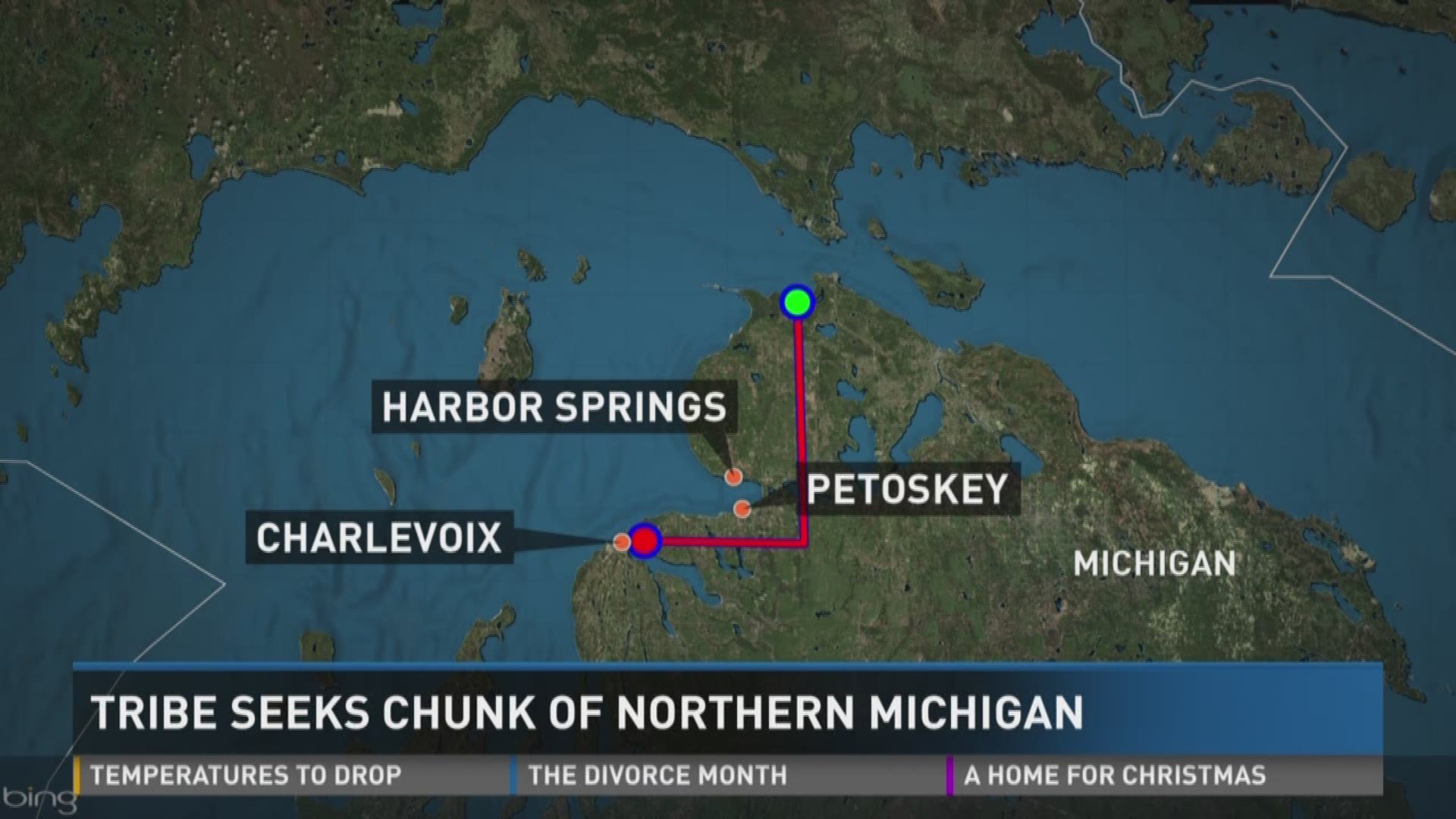

Could the Up North vacation spots downstaters have loved for generations — including Charlevoix, Petoskey, Harbor Springs and Cross Village — become a vast Indian reservation?

A Petoskey-based tribe says it already is and has been for more than 160 years. Now the tribe is asking a federal judge to allow it to assert jurisdiction over the area.

The Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, in a slow-moving, complex federal lawsuit, wants a federal judge to confirm that a huge swath of the northwest Lower Peninsula is its reservation land, a potential ruling that could alter local governance, law and zoning enforcement and other aspects of life for Indians and non-Indians alike.

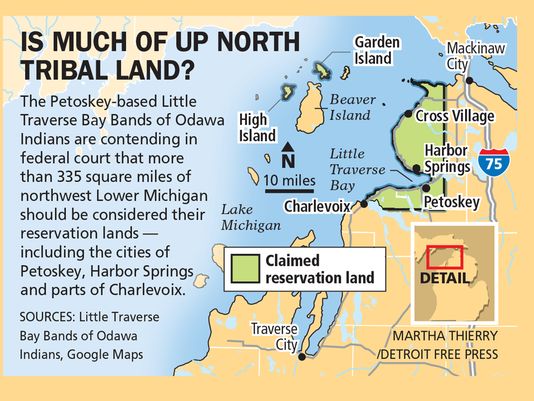

In the lawsuit, filed last year against Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder in U.S. District Court in Grand Rapids, the tribe claims the 1855 Treaty of Detroit between Ottawa and Chippewa Indians and the U.S. government affirmed as reservation land an area 32 miles north-to-south from the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula down the eastern shore of Little Traverse Bay. The 337-square-mile area in question includes Cross Village, Good Hart, Harbor Springs, Petoskey and northern Charlevoix.

It's an issue, the lawsuit claims because Michigan has "refused to recognize the tribe's reservation in a number of ways that threaten the tribe's autonomy and sovereignty, and that violate the 1855 treaty." It cites examples, including:

- Michigan asserting jurisdiction over Indian child welfare matters on reservation lands, in violation of the federal Indian Child Welfare Act.

- Tribal members living in some townships that the tribe asserts are part of its reservation not being exempted from state income taxes, contrary to federal law.

"This would just clarify we have jurisdiction over our citizens within our reservation boundaries," said Little Traverse Bay Bands Tribal Chairwoman Regina Gasco-Bentley.

It would do far more than that, said attorney Lance Boldrey, who represents the Emmet County Lakeshore Association, an affiliation of lakefront property owners and businesses from Harbor Springs to Cross Village. The association has intervened in the case as a defendant, along with the cities of Charlevoix, Petoskey and Harbor Springs.

Local governments, such as townships and cities, would lose regulatory power, Boldrey said.

"You end up with a fairly large class of individuals in this area who are no longer subject to local zoning requirements, signage requirements, business regulations," he said. "If you have a non-Indian who sells a product on the reservation to a tribal member — and you have no way to know — and a dispute arises, that would be adjudicated in tribal court."

Boldrey noted that over the years, Harbor Springs has worked to keep fast-food restaurants out of the downtown area. If the city ended up as part of the tribe's reservation, he said, "a tribal member who buys a lot on State and Main streets could put in a McDonald's at the gateway of downtown, because local zoning doesn't apply."

In other states, expanded reservations resulted in the expansion of slot machines and video gaming into party stores, bars and restaurants — even those not owned by Indians, he said.

If it sounds preposterous that a court could declare almost half of the northern Lower Peninsula an Indian reservation, "We're not chuckling," said Gary Rentrop, an attorney and president of the Emmet County Lakeshore Association.

Federal courts have ruled in favor of tribes in several reservation claims across the country. That includes the recent case of Pender, Neb., which has virtually no Indian population and has historically operated under state, not tribal, jurisdiction.

An 1882 Act of Congress opened portions of an 1850s Indian reservation for sale to non-tribal members, and that was how the village of Pender was established. But the local Omaha Tribe in 2006 enacted a liquor ordinance, and directed non-Indian bars and package liquor stores in Pender to obtain a tribal license and pay a 10% tribal liquor tax. The village and state of Nebraska challenged whether the land was an Indian reservation, and lost before the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year.

"It's being taken seriously," said Petoskey City Council member Kate Marshall, who declined further comment due to the still-pending litigation.

Tribes are often helped by a judicial standard that it's not necessarily what a treaty states, but what the Indians involved understood the treaty to mean at the time, Rentrop said.

According to the Little Traverse Bay Bands' lawsuit, European settlers first contacted their tribe in 1615. "Odawa Indians occupied the territory the next 250 years," the complaint states.

By the 1830s, the U.S. government's Indian policy focused on securing treaties in which Indians handed over their historic lands, removing Indians from those lands, and encouraging non-Indian settlement, the tribe's lawsuit states. During this era, federal Indian agents pressured the Odawa to cede their lands and relocate to unfamiliar western locations.

"The bands of Odawa that today make up the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians fought for the right to remain in their homeland," the tribe's lawsuit complaint states. "In 1835, Odawa leaders traveled to Washington, D.C., in an effort to secure their homeland."

That effort culminated in an 1836 treaty in which certain Odawa and Chippewa bands retained 14 reservations, including a 50,000-acre reservation on Little Traverse Bay, and a reservation consisting of "the Beaver Islands." The bands also reserved hunting, fishing and other rights throughout the area. In exchange, the U.S. negotiators secured more than 26 million acres, about half of which would become the northwestern Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

But the U.S. didn't ratify that treaty as negotiated, the Little Traverse Bay Bands assert. They instead unilaterally modified the reservation clause, time-limiting it to only five years "unless the United States grant them permission to remain on said lands for a longer period."

"The Odawa and Chippewa only accepted this amendment upon assurances from Michigan agent and U.S. negotiator Henry Schoolcraft that the United States would not enforce the five-year limit and the bands could remain on their reservation beyond the five-year sunset," the tribe's lawsuit complaint states. "The Odawa understood Schoolcraft's assurances to mean that they would, in fact, never be removed from the reserved land in Michigan."

By 1854, the U.S. shifted its Indian policy to focus on the creation of reservations. In the 1855 Treaty of Detroit, "the United States intended to secure permanent communities and homes for the bands and to insulate their communities from non-Indian settlers and simplify the government's planned 'civilization' of Indians," the Little Traverse Bay Bands' lawsuit complaint states.

The treaty, Little Traverse Bay Bands officials say, sets out the 337-square-mile boundaries the tribe now asserts, including High and Garden islands in Lake Michigan.

Ensuing decades brought "land frauds (that) plagued the area," but also several instances of the federal government recognizing the reservation boundaries, according to the tribe. Congress passed a law in 1872 allowing tribal members to purchase lots within the 1855 treaty reservation boundaries, and allowing the U.S. government to sell to non-Indians lands within the reservation not purchased by tribal members.

U.S. District Judge Paul Maloney has split the lawsuit in two, first seeking to determine whether the Treaty of Detroit created the reservation with the boundaries the Little Traverse Bay Bands now assert, and whether later acts of Congress diminished or disestablished that reservation.

If the court finds the reservation does continue to exist as described, a second phase of trial would ensue, hashing out the jurisdictional issues that then arise with state and local governments. The first phase alone is expected to extend into the summer of 2018.

"This will take a few years at least," Gasco-Bentley said.

The uncertainty the lawsuit generates could affect non-tribal property owners' quality of life and property values, Boldrey said. Many of those potentially affected have lived, vacationed or owned property for generations on the renowned "Tunnel of Trees," M-119 highway along Lake Michigan from Harbor Springs to Cross Village, he said.

"Does it cause somebody to say, 'I don't want to buy into this uncertainty when I can go buy on Walloon Lake and it doesn't have any of these issues?'" he said. "That directly affects my clients' property values."

Gasco-Bentley sought to calm local residents' fears.

"There's been some false information that's been released out there that has people quite concerned; but a lot of it is not true," she said. "It will not affect the cities or the townships with their law enforcement, their zoning or their laws. (But) our tribal citizens who live within the reservation would have to follow tribal laws and regulations."

The Pender decision in Nebraska particularly shows that even if the tribe is sincere about the jurisdictional issues they are attempting to clarify through the lawsuit, it opens up issues "down the road that no one foresees," Rentrop said.

Contact Keith Matheny: 313-222-5021 or kmatheny@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @keithmatheny.