GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — Diffuse Axonal Injury.

It's a form of brain damage that occurs in about half the patients who experience severe head traumas. A shearing effect happens where all of the neurons in the brain are broken and cannot be repaired.

In the most severe cases of DAI, death is the most frequent outcome. Of the 20% who do survive, all are significantly impaired, dependent and remain in a permanent unaware state.

Despite the grim outcome most DAI patients are presented with, the reason for hope was energized earlier this year when a teenage patient with the most severe form of the condition was transferred from a hospital in St. Louis to Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital in Grand Rapids.

The patient's name was Malachi Griffin. He didn't exactly follow the rules of DAI.

In fact, he broke all of them.

On December 8, 2018, Malachi was preparing to help his uncle, David Freeze, move from Hancock, Michigan, to Memphis, Tennessee. The drive would take them about 15 hours to complete.

"They'd made it over halfway when the accident happened," said Kelly Griffin, Malachi's mother. "I got a phone call and I knew immediately something was wrong and my world was rocked."

Malachi was driving in a pickup truck in the southbound lanes of Interstate 57 in southern Illinois when a car swerved in front of him, forcing him to hit his brakes. He lost control and his vehicle started flipping. Malachi was ejected from the truck and landed on the edge of the median and highway.

The truck tumbled a total of nine times before it came to rest in the center of the northbound lane. It was crushed and the highway was littered with debris and personal belongings.

Malachi's uncle stopped, got out of his vehicle and raced to where Malachi was laying.

His nephew wasn't breathing and didn't have a pulse.

Paramedics arrived at the scene and managed to revive Malachi, before he was airlifted by medical helicopter to Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

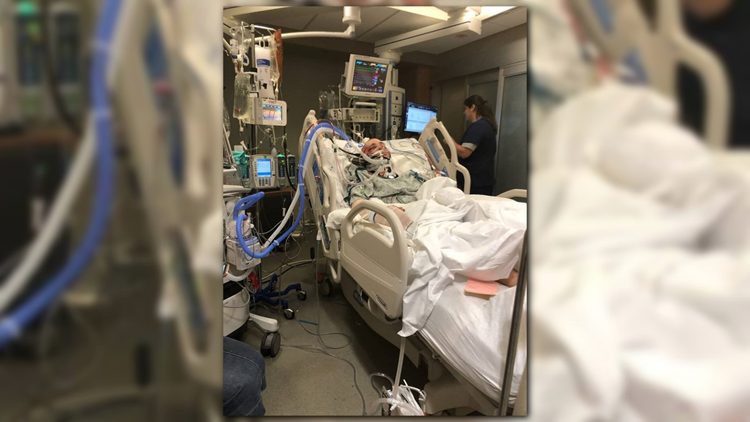

Malachi was immediately placed in intensive care and required a ventilator to stay alive.

Malachi was barely breathing

"We had no idea the magnitude of what had taken place," said Thomas Griffin, Malachi's father. "Nobody told us exactly what had happened."

Thomas and Kelly Griffin began the long drive from Michigan's Upper Peninsula to St. Louis with the hopes of getting their son and bringing him back to Hancock.

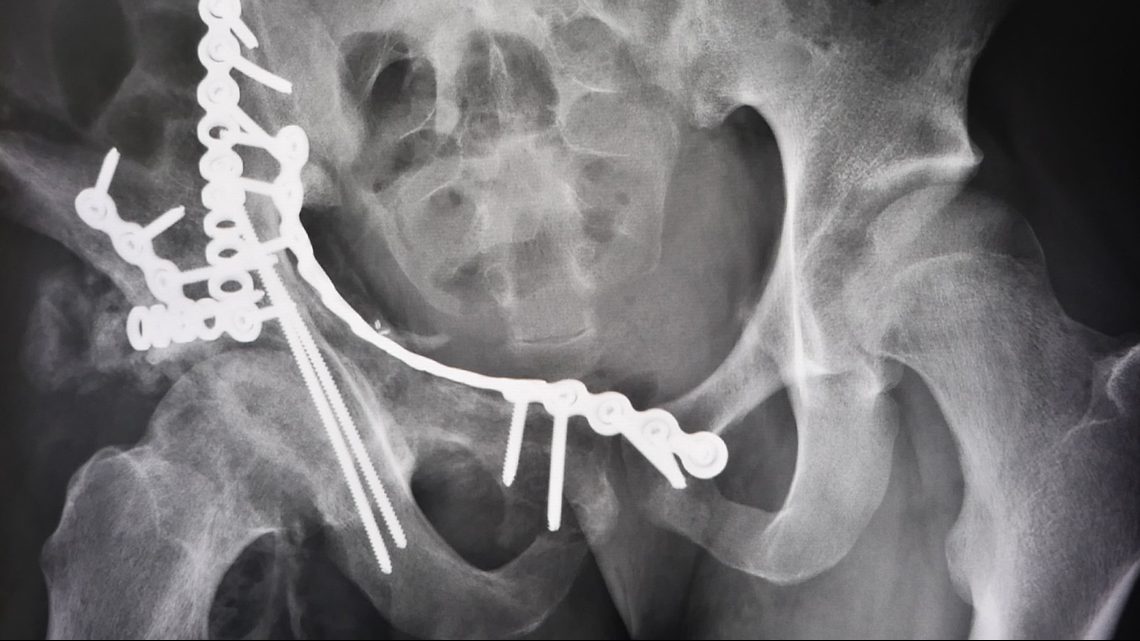

"While we were driving, I took a call from the hospital and they said they needed permission to handle [Malachi's] lacerated liver; they needed permission to do something about the punctured lung; they needed permission to do something about his shattered hip socket and they needed to put his leg in traction," said Thomas. "We became increasingly concerned."

When the Griffins arrived at the hospital, they were escorted to the intensive care unit to see Malachi.

When they entered their son's room, they couldn't believe what they witnessed.

"Our son wasn't even recognizable," said Thomas. "He was hooked up to all kinds of contraptions and was all swollen and bruised.

"His head was shaved and had a brain monitor hooked up to it.

"Nothing prepares you for that."

Thomas said that he and Kelly were with Malachi around the clock for the first few days they were in St. Louis just waiting for him to open his eyes.

Malachi's doctors told Thomas and Kelly some news they didn't want or need to hear.

"They diagnosed Malachi as having Diffuse Axonal Injury," said Kelly. "One of the nurses told us one night, 'What you see is what you're going to get. He's never going to walk out of here.'"

The Griffins say they kept holding on to faith and believing that God was going to do something different.

"You just do what you're told because you don't know what you're doing," said Kelly.

Suddenly, the 'something different' they were hoping for seemed to start happening.

"The doctors told us that Malachi would be in intensive care for three months, but 15 days after the accident, he was moved to the progressive care unit," said Kelly.

Malachi was still unresponsive but he had stabilized to a point where he could advance to the next phase of care.

"When we got to the progressive unit, the doctors told us that Malachi would remain there for two to three months," Kelly said.

But that didn't happen either. Just a few weeks after entering progressive care, Malachi was transferred to Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital in Grand Rapids.

The Griffins chose to see the accelerated form of care as a very positive sign and that their son was going to defy the odds and recover even though they didn't understand how sending him to a rehabilitation facility would help him, given his condition.

"We don't know if he's understanding anything we're saying," Thomas said. "He's not communicating to us; he's not in control of his limbs so how do you go to a rehab facility and take care of that?"

Malachi was airlifted from St. Louis to Grand Rapids in February 2019.

"When he arrived, he wasn't responding to anything," said Dr. Lisa Voss, who is a specialist in pediatric rehabilitation at Mary Free Bed. "He was in what we call autonomic storming which is where the brain is sending off signals that happen after it's been injured, like uncontrolled body temperature and blood pressure.

"So, that's how we first met Malachi, but we never lost hope."

Dr. Voss knew that she and her staff had a lot of work ahead with Malachi, but the first order of business was to get his body back to regulating itself, which they did.

"There's was a board in Malachi's room where the physical therapists placed goals on," said Kelly. "Two of the goals were standing and walking.

"I thought they were nuts. Malachi can't do anything. He doesn't move one body part."

Even though Malachi was still in an unresponsive state, the therapists began working with him every day, getting him up on his feet and making his body walk.

"They were trying to get his brain to re-map," said Thomas. "The more they worked with Malachi's muscles, his feet, legs and hands, the better chance it might try to connect back to his brain.

"They just kept working his limbs hoping his brain would find them."

The physical therapists would hold Malachi in a standing position. One of them in front, one behind, and one on the side, keeping his legs out. They would do this for 30 seconds to two minutes.

"The therapists would walk for him," said Thomas. "They'd move his legs as though he were walking so that if he wakes up, he may remember doing it."

About a month after arriving at Mary Free Bed, Malachi did something nobody expected.

"He started having seizures," said Dr. Voss. "It's not common for kids this far out from a brain injury to develop seizures.

"Often times, the seizures occur either initially, upon the traumatic incident, or within 24 hours to a week later."

Then there was the day when one of the therapists came to Dr. Voss and said, "You know what, I think [Malachi] just kicked me on the side of the bed."

Dr. Voss didn't believe the claim at first.

"I said, 'That's nice. Sometimes, you see something that may not actually be there because you want it so badly to happen.'"

But then it happened again for a different therapist.

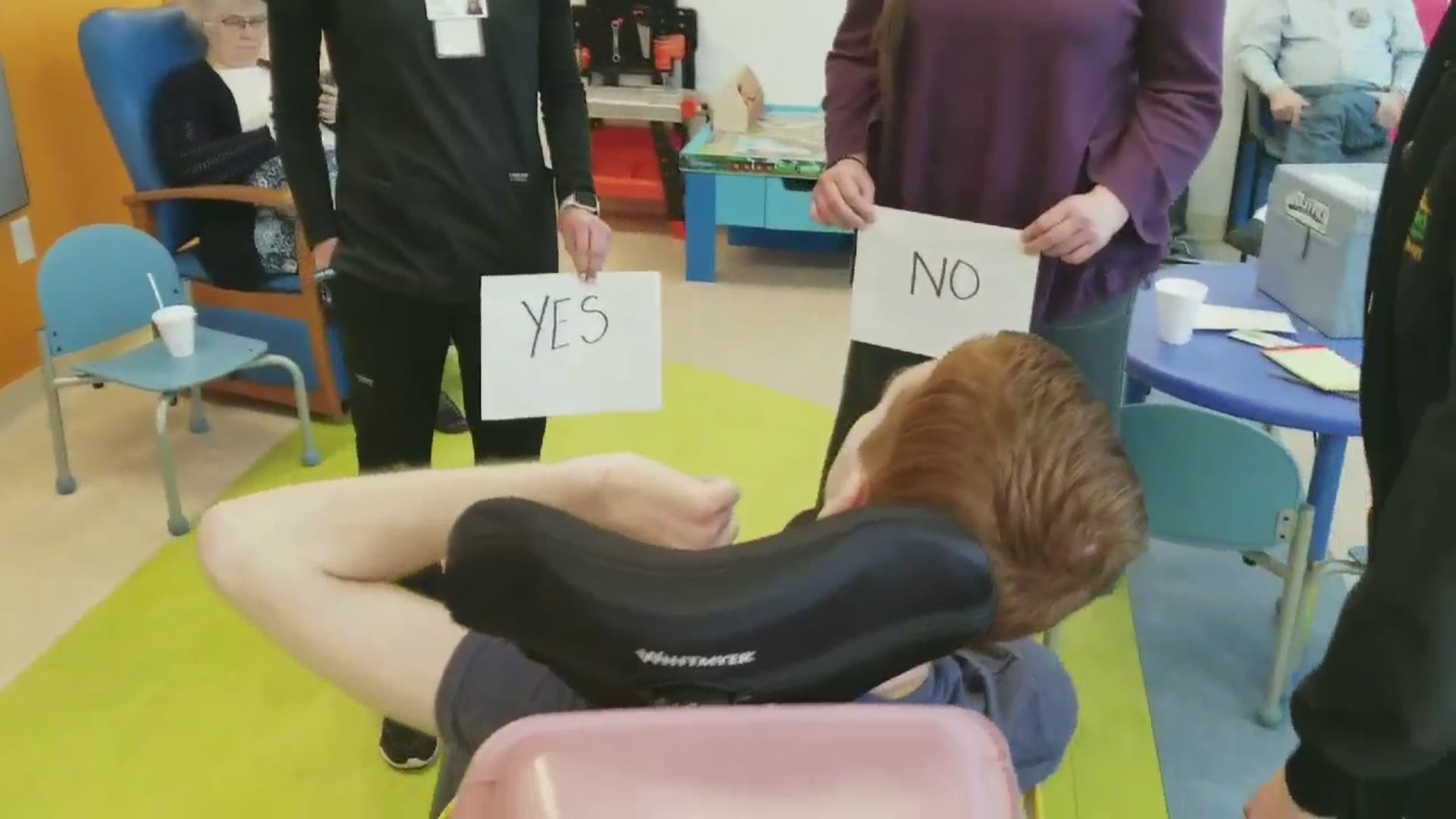

"And it just kept happening," Dr. Voss said, who quickly realized that Malachi may have been trying to communicate with his legs.

"Malachi clearly didn't read the book about how to recover from a brain injury," joked Dr. Voss. "He didn't follow any of the rules."

Malachi still hadn't emerged from his coma, but his family members, along with the medical staff, would ask him questions and he'd answer "yes" and "no" with his legs.

"Everybody was just shocked," said Kelly. "His brain was starting to use what was left over to try to recover."

In March, Malachi woke up.

"Typically, when people recover from a brain injury, they follow very specific steps," said Dr. Voss. "We learn all that in medical school.

"Well, Malachi decided to skip all that."

Improvement continued to rocket from that point forward.

"It went from communicating with his legs to being able to respond and follow commands," added Dr. Voss.

"We later found out that crossing mid-line with your leg or foot is one of the hardest things for them to teach and that's where he was starting," said Thomas.

It didn't take long for him to start trying to form words.

"Just getting 'Hi' out literally took everything in him," said Kelly. "He would have to push his whole body forward to get [words] out.

"Two days after he said, 'Hi', he said, 'Hi Ma,' and then he said, 'Hi mom."

Then came the day he recognized his parents.

"When the therapists asked him the question, 'Is your mom and dad here,' and he answered, 'Yes,' I just lost it," said Thomas. "I knew at that point things were going to work out."

As the days and weeks passed, Malachi continued to form words and talk and began walking with help up and down the hospital hallways. In late April, he was aware and in control of his extremities enough to start bouncing a basketball back and forth with his dad.

Then came the day he started to remember how to play the card game Euchre and wanted to take on anybody who was prepared to play.

"I clearly remember the day when I went in and he gave me a fist-bump," said Dr. Voss. "That was yet another day when I had to leave his room to go somewhere and cry.

"He's Miracle Malachi."

"I should have died in that crash but I didn't," Malachi said. "God has some purpose."

When Malachi found most of his words, he started talking about wanting to go home, and he wanted to walk there.

"It's 503 miles," joked Malachi, referring to how far it was from Grand Rapids to Hancock. "I want to be home with my family; that's why I said I'd walk."

When asked what he wanted to do first when he got home, Malachi said, "Eat mom's home cooked food; stroganoff and Greek Spaghetti. It has bacon in it and four different kinds of cheese."

On June 7, Malachi had recovered enough to leave Mary Free Bed.

"I told everybody I think we need to retire his room," said Dr. Voss. "We need to put up a sign, hang a jersey that says the room is dedicated to Malachi."

Escorted by his parents, and with the aid of only a cane, Malachi walked out of his room for the last time and proceeded down the hallway. Flanked along the sides of the hallway were dozens of his family members, doctors and supporters crying, cheering, playing music and blowing bubbles, making sure the moment was celebrated.

Thomas and Kelly say Malachi will continue doing weekly physical therapy at a facility near his home. He'll endure occupational therapy four times and speech therapy three times.

"We know that we still have a long road but we're on that road," said Kelly. "He's our miracle and we don't take that for granted."

Malachi was helped into his parent's vehicle which was parked in front of Mary Free Bed. As the car slowly pulled away, he smiled and waved goodbye, as he began his trip home back to Hancock.

"He's thrown things at me that I would have sworn were going in the wrong direction and then he just pulled it around," said Dr. Voss. "Clearly, he still has a reason to be here.

"He has something he's supposed to do in this world."

If you know of a story that should be featured on "Our Michigan Life," send a detailed email to 13 On Your Side's Brent Ashcroft: life@13onyourside.com.