At the Greyhound bus terminal in Detroit in January, federal immigration agents stopped and questioned a Latino couple on their way to Grand Rapids. As a result, 23-year-old Walter Pena was arrested because he could not prove his immigration status.

"It was racial profiling," said Abrielle Sebeny, 21, the fiancée of Pena. "It's not just ... they shouldn't treat Spanish people like that."

That same month, passengers on another Greyhound bus traveling from Detroit were questioned at a stop in Ohio; those who could not prove that they were living in the U.S. legally were detained.

A Greyhound bus pulls out of the Detroit bus terminal on April 25, 2018, in downtown Detroit on 6th Street near Howard Street. (Photo: Niraj Warikoo)

Last month, at the Amtrak train station in Dearborn, Jeffrey Nolish, a 37-year-old U.S. citizen who is Latino and serving in the military, said he was the only person on a train interrogated by two U.S. Border Patrol agents who boarded the train with a police dog.

Many Latinos and immigrants say that these types of sweeps by Border Patrol agents are playing out in metro Detroit with more frequency because of the Trump administration's increased targeting of immigrants. Eighty-two percent of foreign citizens stopped by Border Patrol in Michigan are Latino, says the ACLU.

Civil rights advocates call it racial profiling, and targeting of poor immigrant populations who use the mass transit system. But the entire state of Michigan falls within a 100-mile Border Zone that gives federal immigration agents extra power to search people or vehicles. For many, the result has been stressful, and when resulting in arrests or detention, devastating.

Jeffrey Nolish says he was the victim of racial profiling while traveling on an Amtrack train on April 14, 2018. (Photo: Jeffrey Nolish)

"It impacts the entire community, regardless of your status," said Angela Reyes, executive director of the Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, which is based in southwest Detroit. "We have Border Patrol sometimes sitting outside of our building and we have to go out and ask them to leave."

At the Greyhound bus terminal near the entrance to the Lodge Freeway in Detroit, Border Patrol agents with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) often patrol the station, observing passengers and questioning them.

In response, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Michigan and other ACLU branches sent a letter in March to Greyhound asking it to stop allowing immigration agents to board buses to questions passengers, saying it violated their constitutional rights. Under U.S. border regulations, agents can patrol and stop people 100 miles from an international border, which includes the entire state of Michigan and about two-thirds of the U.S. population. In a lawsuit filed in 2016, the ACLU is also asking CBP to provide data on its stops in Michigan.

According to data collected by the ACLU, there is a clear pattern of agents targeting Latinos, including citizens, despite the fact that the vast majority are not criminals:

- Almost one in three people processed by Border Patrol agents in Michigan are U.S. citizens.

- 82% of foreign citizens stopped by CBP in Michigan are Latino.

- Less than 2% of foreign citizens stopped in Michigan have a criminal record.

"The common thread in the reports received by the ACLU of Michigan is that CBP agents operating on Greyhound buses focus on persons of color and never give passengers a reason for the stop," said the ACLU in its letter. "This data strongly suggests that CBP is using ethnicity as the basis for its stops."

Similar incidents this year in Florida, New York, and Maine have gotten widespread attention, in part through videos documenting the encounters. While accusations of profiling by immigration agents are not new, they have increased since the administration of President Donald Trump toughened immigration enforcement.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection denies it targets people based on race.

"It is the policy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection to prohibit the consideration of race or ethnicity in law enforcement, investigation, and screening activities, in all but the most exceptional circumstances," said CBP spokesman Kris Grogan. "CBP is fully committed to the fair, impartial and respectful treatment of all members of the trade and traveling public."

Detroit Greyhound bus station in Detroit in April 2018. (Photo: Niraj Warikoo)

Stopped, detained and confused

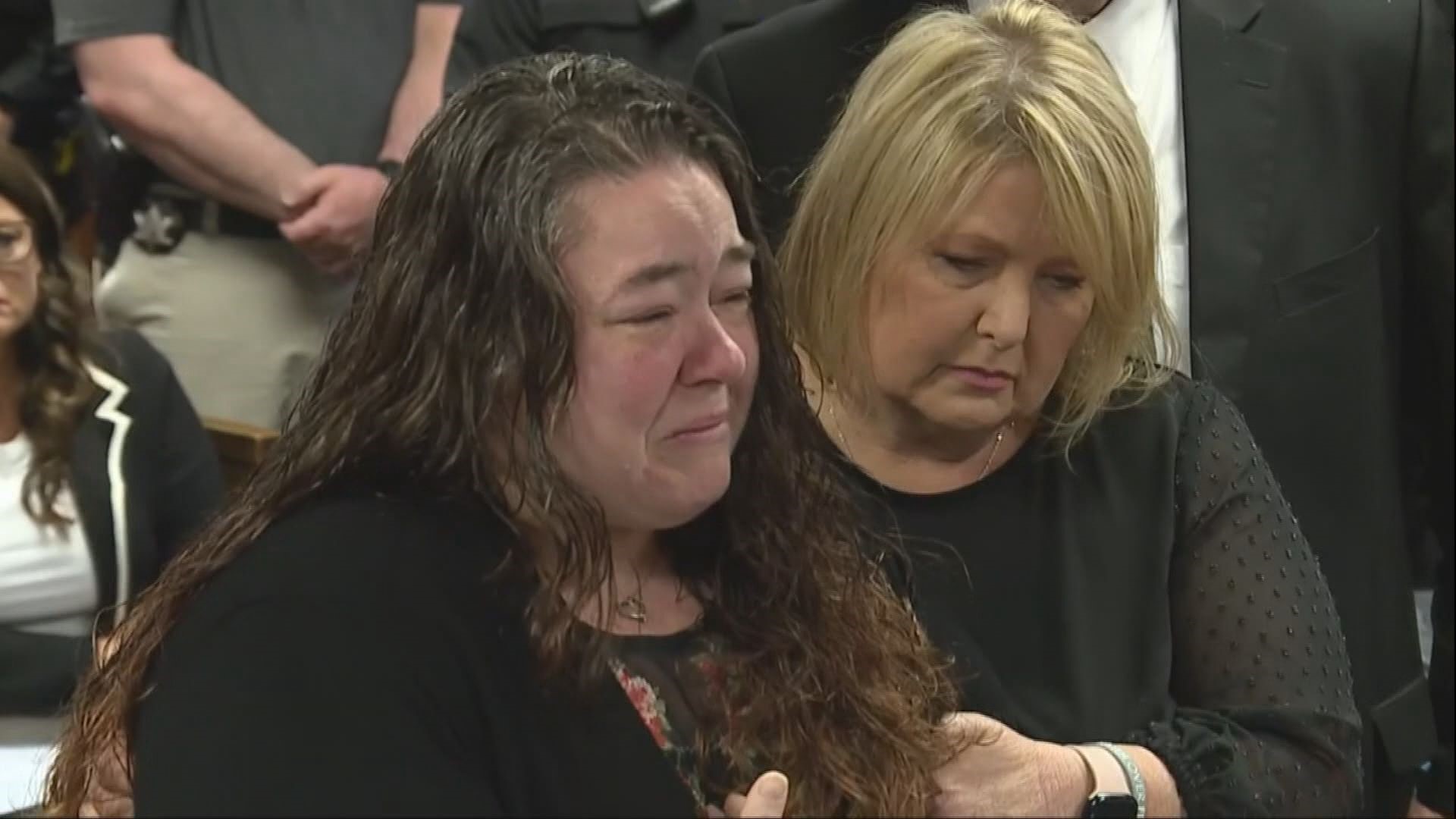

For Sebeny, a U.S. citizen born in Peru, the experience of being profiled and her boyfriend arrested "was probably the worst thing that ever happened to me."

Sebeny said that she and Pena, an immigrant from El Salvador who is undocumented, were waiting to transfer to a bus to take them from Detroit back to Grand Rapids, where they live.

She said three agents with Border Patrol came toward her and Pena after spotting them and started asking questions such as: "Where are you from?" and "How did you enter the U.S.?"

Pena "doesn't speak English too much," Sebeny said she told the agents when they started directing their questions to him. "I can answer for you if you want. He told me to shut up, I'm not asking you anything."

The agents then arrested Pena, telling Sebeny that they "will be back in 15 minutes to an hour," but no one ever came back, leaving her confused and worried.

"I waited at the station and he never came. I called the number they gave me and he never came. I'm not from Detroit. I didn't know where to go. I had to stay in a hotel for a week."

Like many immigrant detainees, Pena was transferred several times to different jails. He was eventually released on bond and is currently living in Grand Rapids, said Sebeny. An undocumented immigrant, the construction worker came to the U.S. from El Salvador seven years ago and hopes to remain in the U.S. with Sebeny.

"They're creating a climate of fear," said Abril Valdes, an immigrant rights attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan. "The problem is, they're stopping people based on racial profiling."

In addition to being discriminatory, such practices don't help in protecting the public and will make Latinos and immigrants more reluctant to trust and work with police.

"How is installing fear in people any benefit to anyone?" Valdes asked. "How is this protecting us?"

Travel companies under pressure

In a March 21 letter to Greyhound, ACLU attorneys, including Michael Steinberg of the Michigan ACLU office, criticized "Greyhound’s practice of permitting CBP agents to routinely board its buses to question passengers about their citizenship and immigration status."

Citing several cases, including two in Michigan this year, the ACLU said: "These intrusive encounters often evince a blatant disregard for passengers’ constitutional rights and have even resulted in CBP agents removing passengers from buses and arresting them. Greyhound’s cooperation with CBP is unnecessarily facilitating the violation of its passengers’ rights."

Valdes said the ACLU wants Greyhound to exercise its Fourth Amendment rights and tell federal agents to not board its buses.

A map from the ACLU shows the U.S. government's 100-mile Border Zone. In this map, it's the area colored orange. The entire state of Michigan is included in the zone (Photo: ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union))

In a statement to the Free Press, Greyhound spokesperson Lanesha Gipson said: "We understand the ACLU’s concerns and those of our customers with regard to this matter. However, Greyhound is required to comply with the law. We are aware that routine transportation checks not only affect our operations, but our customers’ travel experience, and we will continue to do everything legally possible to minimize any negative experiences."

Greyhound has opened a dialogue with the Border Patrol to see whether there is anything that can be done to balance the enforcement of federal law with the dignity and privacy of our valued customers."

Gipson said that Greyhound is following federal laws that give federal agents more power in areas within 100 miles of an international border, which includes the entire state of Michigan, to inspect vehicles, aircraft, and rail cars.

Grogan, a spokesman for the CBP, also cited the 100-mile zone in federal law in defending Border Patrol actions on Greyhound buses.

"For decades, the U.S. Border Patrol has been performing enforcement actions away from the immediate border in direct support of border enforcement efforts and as a means of preventing trafficking, smuggling and other criminal organizations from exploiting our public and private transportation infrastructure to travel to the interior of the United States," Grogan said. "These operations serve as a vital component of the U.S. Border Patrol’s national security efforts."

"Although most Border Patrol work is conducted in the immediate border area, agents have broad law enforcement authorities and are not limited to a specific geography within the United States," he said. "They have the authority to question individuals, make arrests, and take and consider evidence."

The presence of Border Patrol is also seen in train stations.

Nolish said he experienced profiling one day last month at a train stop in Dearborn.

Nolish, who was born Miguel Guerrero in Colombia, came to the U.S. as an adopted child by parents in Huntington Woods. He said he has been taking the train since he was 14 years old and never had any problems. But on April 13, he was traveling back to Detroit from Chicago when two Border Patrol agents and their dog boarded the train at a scheduled stop in Dearborn.

Walking down the aisle, the agents zeroed in on Nolish, who was sitting next to his friend, Lauren Hood. The police dog sniffed around.

"They stopped by us and stopped by our seats," Nolish said. "There was an absolute focus on me. ... They looked at my mannerisms, my lips moving."

Nolish said the agents then walked down the aisle, and "when they came back, stopped by their seats again. They ignored Lauren and looked at me.

"Where are you coming from?" an agent asked, Nolish recalled. "I said, 'Chicago.' He looked at me and said: 'Where did this train start? Is that where this train started? Was it Chicago?' I said, 'yes,' and he kind of stared at me."

The agents left without asking Nolish for his ID, which happens in other cases, say immigrant advocates.

Hood confirmed Nolish's account of what happened. A CBP spokesman did not comment on the case, but said their agency doesn't racially profile.

Nolish, a policy adviser at the Southwest Detroit Community Benefits Coalition who serves in the Michigan Air National Guard and U.S. Air Force and is running for state representative in the 4th District in Hamtramck and Detroit, said of his experience: "There are people who are naturalized citizens who are seen as a threat. We have these restrictive policies set up to protect the country and they make people feel like they're the problem. These policies suggest that my skin color is a detriment. ... and I think that's wrong."

Amtrak spokesman Marc Magliari said "Amtrak cooperates fully with federal authorities and federal law. Amtrak customers 18 years of age and older must carry valid photo identification."

Magliari did not comment on the issue of racial profiling.

A reminder of passenger rights

At the Greyhound terminal in Detroit, immigrant advocates have been handing out flyers reminding passengers of their rights. Border Patrol agents often appear at the station twice a day, around 11 a.m. and 5 p.m., said Valdes of the ACLU.

Passengers wait in line to board a bus at the Detroit Greyhound bus station at 1001 Howard St. on April 25, 2018. (Photo: Niraj Warikoo)

On a recent Wednesday, two Border Patrol agents, a man and a woman, were seen entering the station shortly after 7 p.m. to inspect passengers.

As they entered, one of the immigration agents fist-bumped with an Amtrak employee and the pair then stood by a row of telephone booths watching closely a row of passengers lined up to board a bus for Chicago.

No arrests appear to have been made on that day.

"I feel hurt," said Sebeny, the 21-year-old citizen whose husband, Pena, was arrested at the same station in January.

Sebeny, who is expecting a child with Pena, is now fighting for her husband to stay in the U.S.

Contact Niraj Warikoo: nwarikoo@freepress.com or 313-223-472. Follow him on Twitter @nwarikoo

►Make it easy to keep up to date with more stories like this. Download the WZZM 13 app now.

Have a news tip? Email news@wzzm13.com, visit our Facebook page or Twitter.